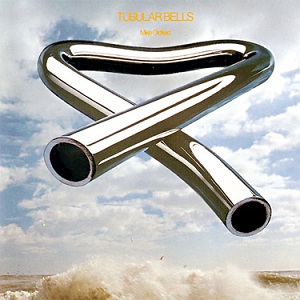

Mike Oldfield

Virgin Records (1973)

This was a pretty big record for me. It shaped a lot of my musical tastes at just the right time, pointed me in lots of different directions, down a few a few cul-de-sacs too, and gave me my first teenage musical hero.

This was a pretty big record for me. It shaped a lot of my musical tastes at just the right time, pointed me in lots of different directions, down a few a few cul-de-sacs too, and gave me my first teenage musical hero.

I came across it in round about 1984-85, aged maybe 13 or 14. I’d been given records for Christmas by a groovy auntie and every now and then I spent my pocket money on cassettes of dorky stuff I thought my parents or my music teacher would approve of. Like Handel’s Water Music. Or like Dermot “Dancing Fingers” O’Brien (I was a student of the accordion from an early age). Tubular Bells was the first music I can recall buying that was just for me.

The album entered my life when I was an impressionable second year high school pupil. We had an English teacher who was younger than the rest, a bit off-the-wall, bursting with mad ideas. One term’s assignment, for example, was to invent a pop band. We had to come up with a name, write their songs, design their posters, write a gig review etc. The next term he set us up as a university style debating society, which went about as well as can be imagined.

One day he came to class with an 8-track player and a bag of cassettes he’d bought that weekend. He was evidently extremely pleased with himself and he proceeded to give us a one-man show-and-tell. He sat at the front of the classroom and raved about the technical superiority of the eight-track system and, with diagrams, demonstrated how the thing worked. The tape in the 8-track was ingeniously looped so that you never had to turn it over to play the other side. It was designed specifically for playing music in cars – I think he drove an old Ford Cortina, which was pretty retro even then.

The one album he played was Tubular Bells, played the whole thing in class. He told us all the stories – Oldfield the boy genius playing all the instruments, Richard Branson and the start of Virgin Records, five years in the top 40, The Exorcist etc.

I was utterly electrified. I’d never heard anything like it. I lapped it all up: the music, the lore, the lot. I adored the album immediately and after my next birthday, armed with record tokens, I made the trip to John Menzies…

John Menzies in the Plaza in East Kilbride town centre was a major pocket-money magnet. Downstairs was all sweets and crisps, books and magazines and stuff to stock your school pencil case. Upstairs was toys and games, music and video (LaserDisc!). It was always chock-full when I started making regular Saturday afternoon trips with pals, cash from grannies and aunties and chores burning holes in our pockets.

There were a few shops in East Kilbride that sold music back then – but they were generic places like Boots and Woolworth’s that stockpiled Greatest Hits records and top 40 stuff. I wasn’t cool enough to go anywhere near Impulse, the only proper record store in town. It was a hang out for a certain kind of kid. Stunt hair. Stunt shoes. Fashion and a fuck-you attitude. Perhaps piercings. Was it punk? Was it post-punk? Was it New Romantic? Was it indie? Whatever it was, peevish wee spods like me who listened to accordeon music weren’t it. I was barely even cool enough for Menzies. I didn’t dare go anywhere near.

In fact, I never felt entirely comfortable anywhere in the town centre. I still don’t. As well as the post-punk/ new romantic mob at Impulse, casual football culture was finding its moment too. Swaggering tribes of well-togged youngsters roamed the place – sharp wee guys dressed in Pringle sweaters and “waffle” trousers, looking for trouble. Everyone had to have a look. I always felt conspicuously, blandly different, an awkward wee alien boy dressed by his maw.

Eventually, I discovered my own refuge in the music section of East Kilbride Central Library. People with sharp haircuts and clothes with names never seemed to go there. Hardly anyone did, especially when it was temporarily relocated to the basement of the Civic Centre. I loved it down there. I went every week. I prized my four yellow Music Library tickets and would spend hours browsing every Saturday, then leave with a full fresh compliment of albums tucked under my arm, their see-through protective sleeves slipping awkwardly all the way home. I’d spend the rest of the afternoon listening and studying liner notes, absorbing facts and details, tracing conductors, personnel, songwriters, producers, for any kind of clue as to what I should go looking for next week.

So what prompted me to want to own my own copy of Tubular Bells when I had a ready supply of free music on tap from the music library? I suppose it was a realisation that perhaps I wouldn’t want to take it back, that this was a piece of music that I wanted to live with. I wanted not only to possess this music, but to inhabit it. My world hummed with it for months. I fantasised about playing the mandolin and the glockenspiel. I wanted to own a set of tubular bells. I was going to be a composer. It was a visceral longing to get inside and understand the textures of the music. Incredible feeling.

It’s the very same copy I bought in John Menzies all those years ago that I’m listening to now. It still sounds like nothing else on earth, but I can more easily trace the paths that run through and around it. I’m struck by how folky and mellifluous it all sounds. All those mandolins and 12-strings, those gentle melodies, those rolling rhythms. The influence of Philip Glass and Terry Riley is apparent, but doesn’t dominate – there’s no trace, for instance, of the hard city edges of the New York minimalists beyond those repetitive arpeggiating piano and organ lines that weave through the opening sections. Some of Tubular Bells suggests introspective English pastoral rock music, the likes of Nick Drake, Fairport Convention, Jethro Tull, Pentangle etc, without sounding much like any of them. You could call it folk minimalism if you like, but mostly Tubular Bells just sounds like itself.

Thanks to the East Kilbride Music Library, I went through a period of several years obsessively listening to all Mike Oldfield’s records to date. Ommadawn (which I never really warmed to), Hergest Ridge (even less so), Five Miles Out, Crises, Discovery, the live one, the orchestral one, etc. I liked everything he did – not for the music so much as for him. There was something about the man himself that I heard in his music that I completely identified with. Maybe it’s just something that happens to you when you’re a particular age. You need a spirit guide, some kind of hero to project all your desires and ambitions on to. Someone to point the way.

Mike Oldfield felt like my kind of guy. I liked the tone he set in his music. I was to hear it later in others, too. Bill Frisell, maybe. Ornette Coleman. Erik Satie. These are people whose music, for me, is about more than just the music. They seem to open up something about themselves in the music they create in a way that deeply affects me. There’s certainly an honesty and integrity to it, but you kind of expect that of all artists – I think what I’m getting at is about more than just self-expression. Good artists offer us a way of feeling about the world – because of who they are, because of how they feel, and because of how they can transform that feeling into art – that wouldn’t otherwise exist. This is truly what the “creative industries” create: ways of being, ways of seeing.

Ways of hearing, too. I love the journey that listening to this album has taken me on, even though I’ve seldom returned to Oldfield’s music since then. Tubular Bells opened my ears at the right time, but more than that, I think it showed me the kind of person I wanted to be: a bit of a freak, perhaps, a bit of an outlier, of his time, happy to be nothing more, nothing less than just like himself.