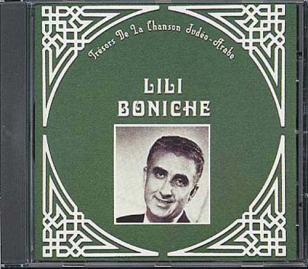

أنا في الحب

By Lili Boniche

The song begins with a long plaintive violin solo over tremolo piano. It could be something from the Warsaw ghetto, the Russian steppe, something like Loyko, maybe? – somewhere familiar to the central Europe folk tradition. The violin solo ends with a flourish in the piano. The clarinet takes over, unaccompanied, with a low trill. We’re still in the same middle European territory, but darker maybe. Breathy and woody, it feels like centuries of sadness and yearning have found their expression here. The piano returns and a syncopating triple rhythm (a malaguena?) in the pizzicato violin jolts you onto the dancefloor of a rundown old cabaret, maybe, in flamenco heels, with your partner now, just beyond your reach. The piano and the violin are adversaries, toying with time, like dancers acting out a tragic love story. After a short, brilliant cadenza played by the pianist, now with a rose clenched between his teeth and thrown to the ground in a fit of pique, everything slows to a heartbeat, and introduces the first we hear of the singer, Lili. He delivers a long one-breath vocalise – a muezzin calling the faithful to prayer, a heart spiked by a discarded rose, a lost gypsy soul. He is joined in his cry by the violin, which darkly, almost seductively, lurks around and behind the voice as it spins around and around, the soul and its shadow, a dazzling romantic duet. And as the band kicks in with a swaggering paso doble run-through of the melody, Lili returns, at last, with the line: Ana fil houb. I’m in love.

The song begins with a long plaintive violin solo over tremolo piano. It could be something from the Warsaw ghetto, the Russian steppe, something like Loyko, maybe? – somewhere familiar to the central Europe folk tradition. The violin solo ends with a flourish in the piano. The clarinet takes over, unaccompanied, with a low trill. We’re still in the same middle European territory, but darker maybe. Breathy and woody, it feels like centuries of sadness and yearning have found their expression here. The piano returns and a syncopating triple rhythm (a malaguena?) in the pizzicato violin jolts you onto the dancefloor of a rundown old cabaret, maybe, in flamenco heels, with your partner now, just beyond your reach. The piano and the violin are adversaries, toying with time, like dancers acting out a tragic love story. After a short, brilliant cadenza played by the pianist, now with a rose clenched between his teeth and thrown to the ground in a fit of pique, everything slows to a heartbeat, and introduces the first we hear of the singer, Lili. He delivers a long one-breath vocalise – a muezzin calling the faithful to prayer, a heart spiked by a discarded rose, a lost gypsy soul. He is joined in his cry by the violin, which darkly, almost seductively, lurks around and behind the voice as it spins around and around, the soul and its shadow, a dazzling romantic duet. And as the band kicks in with a swaggering paso doble run-through of the melody, Lili returns, at last, with the line: Ana fil houb. I’m in love.

There’s no way my description can do justice either to the song and the musicianship that realise it so perfectly, or to the impact that it had on me when I first heard it. It was visceral and immediate. It was sung in Arabic, but I got the picture. This was the story of a heartbreak of tragic proportions, of louche late-night emotions given free reign, a wandering soul lost among the centuries and the continents. It was a song that seemed to celebrate melancholy, to revel in sorrow. It gave voice – beautifully, agonisingly – to the best and the worst that our heart is capable of.

Whatever I was doing when that song came on, it had to stop in order that as much of what was happening in the vibrating air around my head could be communicated via the clumsy apparatus of brain and ears, directly to my core.

It was the height of summer 2003 and my then girlfriend C- and I were in a seafront cafe/ restaurant in Dahab, a ramshackle resort in Sinai on the Gulf of Aqaba in the Red Sea. We had come via Cairo for a fortnight’s scuba diving. One of C-‘s dive buddies from her advanced scuba course, who was also staying at the same hotel as us, was there. They were talking about diving, I guess.

I had nothing much to offer the conversation. I had enrolled in a beginners’ scuba course and found out on the first day that being underwater wearing all that weird gear really wasn’t for me. It meant that I could tune out the chat, and absorb more of what was going on around us.

I’d been to Dahab before, nearly ten years before, with my Swiss-Lebanese girlfriend Ch- at the end of our time at Regavim. We stayed for a week in a concrete chalet and I contracted food poisoning from some dodgy sahlab. She spoke Arabic as one of her three native languages, which proved useful on occasion. Dahab is a Bedouin village that was “discovered” by Israeli soldiers when Sinai was occupied by Israel in the 1960s. Since then, it has been a place for hippies, backpackers, divers (and dodgers) who want to avoid (or can’t afford) the charms of Sharm el Sheikh further down the coast. It was interesting to note the changes all these years later – more businesses, more name hotels, more money, and a proliferation of scuba diving schools – and to try and see past that to what remained of the old place. God knows what it’s like now.

My first diving lesson was a day’s worth of obligatory safety chat, video watching and pally reassurances from a pair of complacent New Zealander girls and instruction from a serious looking Arab guy. I hated it all from the get-go, but I was keen to disperse my initial skepticism and give it a good try. I liked the sound of scuba diving. My uncle Dave was a brilliant diver in his day and I looked up to him enormously. I also wanted it to be a thing that C- and I did together.

But the reality was too much to bear. One of the exercises they make you do early on, to test your suitabilty for scuba, is a buoyancy test. You go out into fairly deep water and lie back and ‘just float’ for 30 seconds. But as soon as any water got into my mouth, eyes, nose or ears, I flinched and panicked and sank, sending a spray of water over everyone. I tried again. Same thing. I tried again. Same thing. I was getting flustered. The New Zealanders were getting impatient. “It’s easy. Just relax. It’s easy if you just relax.” I tried again. I couldn’t do it. And I knew they hated me for it.

We decided to come back to the buoyancy later so that we could get on with the essential business of using the scuba gear. The whole experience of being underwater with a pipe in your mouth and a bunch of stuff strapped to your back to keep you alive is not a natural one. For those who do it, I guess, it’s a means to an end, a bit like putting on the seatbelt in a car before you go for a drive, or clipping in to a pair of pedals before you go for a bike ride. I felt millimeters from death at all times. It was terrifying and claustrophobic, like being buried alive, like my lungs were about to become flooded with water at any moment. My lungs and brain and eyes couldn’t work together to convince each other that I wasn’t about to die right now.

Then, just when you’ve started to get used to the life-saving genius of the scuba gear, they make you take the whole thing off and put it back on again under water, while sharing someone else’s air pipe.

Scuba has developed its own primitive sign language so that you can communicate with your buddies. Giving and receiving thumbs ups is pretty constant, particularly in these early, fraught stages where anything can go wrong and the more experienced divers need to know that you’re ok and not about to drown. I managed eventually to unclip and unshackle the oxygen tanks from my back, I think, and at each stage the instructor was giving me the thumbs up with a questioning look, and I was returning it – but with a kind of white-eyed terror that only deepened with every thumbs up lie I signalled in return.

After that, to my relief, we went snorkelling, which I liked a lot. I liked the flippers – sorry, fins – that seem to propel you effortlessly through the water, and I loved being able to see the world under the waves. But that was real air I was breathing through that wee tube, not some bottled, Matrixy virtual air, and I could poke my head up from the sea surface and feel like I was back in my own world again. No apparatus, no clips and belts, no tanks of oxygen, no pipe down my throat.

When we got back to the base, I secretly left the decision on whether to return and finish the course to my subconscious. If I had bad dreams that night, I would listen to them and act accordingly. On the other hand, if I slept soundly, then I’d get over my bullshit pansy-ass flenchy-flinchy flip-flopping and get with the fucking programme.

Well that night, I dreamed the terrors of the deep and woke sobbing. I went back to the scuba centre the next morning, who were pretty good about giving me my money back, fortunately, bid goodbye to C- as she hooked up with her advanced diving pals, then went to go and lie out like a mad dog somewhere in the heat of the midday sun getting sunstroke while reading The Lovely Bones.

When the song came on in that restaurant, I was utterly lost to it, possessed by it. As soon as it finished I asked the waiter in the restaurant to find out what it was. He didn’t know. The best he could do was to tell me he thought it was from a compilation called Buddha Bar, which I bought from one of the many counterfeit CD shops in town as soon as they opened the next day.

The rest of the stuff I heard that evening was forgettable. A sort of clubby, loungey update on the easy listening exotica of the 1960s that brought the likes of Edumdo Ros and Mantovani to worldwide prominence. I have no idea what a Buddha Bar is, if it’s a franchise, a venue, a state of mind, nor do I have any idea about the identity of Claude Challe, who lends his name to the enterprise, or what the whole shebang has to do with Buddhism. But it brought Lili Boniche into my life, and for that I will always be grateful.

None of this backstory lends any credit or insight into the song, of course, but listening back to it, I am transported once more. I can still see the faded cabaret, the empty dancefloor, the discarded rose and the louche lost lover, singing his soul back to health with an eternity of longing and centuries of musical lore to draw upon for strength and inspiration.

I bought the original album from which the song is taken as soon as I could get to an internet-enabled computer with my Amazon account details. Trésors De La Chanson Judéo–Arabe. The title made a lot of sense of the music. Lili Boniche was still alive then; he died some five years later, in 2008. Before he did, he recorded an album with Bill Laswell called Boniche Dub, which you can hear here.

Ana fil houb. I listened obsessively to that song for months as I travelled back and forward to Edinburgh, working on a very iffy freelance contract, the fabric of my relationship with C- disintegrating by slow degrees, day by day, less in love.

Ana fil houb always took me to a magical place, where heartache and sorrow and loss are transformed into inner landscapes of untouchable beauty, where sad feelings fit like old clothes, and where language of any kind is inadequate. Only gesture, melody, rhythm, timbre, tone hold any sway.

Ana fil houb. I learned the meaning of the phrase exactly two years later, the summer I finally fell out of love with C-. I took a trip across Canada and met up with Ch- in her adopted Montreal. I played it to her on the car stereo as she drove round showing me the parts of the city she loved best and I longed, as I always did, to know what it felt to be the singer of that song.