A fantastical journey through Glasgow’s canal hinterland

This is the text of a talk I delivered at the National Theatre of Scotland for Doors Open Day, September 2017, looking at the history of the site of their new “creation centre” Rockvilla and the surrounding area, including Speirs Wharf, Possil, Lambhill and Maryhill.

Welcome to Rockvilla, the brand new home of the National Theatre of Scotland.

I’m here partly because I used to work here. “Here” meaning the National Theatre of Scotland; not “here” at Rockvilla. I started just as NTS was gathering momentum before its opening series of productions, “Home”. I ran the website and produced the programmes, brochures, various bits and bobs. Happy days.

One of the first things I produced at NTS was a publication called “From Home to Here”, a lavish piece of trumpet-blowing from an organisation that was barely two years old at the time but clearly had big ideas.

The title was telling. Right from the beginning it was evident that the National Theatre of Scotland was deeply concerned with matters of belonging, matters of place.

I left the NTS shortly before the Rockvilla project got underway so I’m as new to this place as you are. In the years since, two of my jobs have involved working in historic canal-side buildings in Glasgow so I’ve picked up a fair bit of local lore which I’m going share with you, on a “fantastical journey through time”, as it were, in a big anticlockwise loop, beginning and ending here at Speirs Wharf, taking in as much of the surrounding area as I can get away with.

Matters of place have always been integral to what NTS does, which is the genius of the “theatre without walls” model that was built into its DNA. It’s not just about its touring remit, its responsibility to the communities of Scotland, its role as cultural ambassador – artists constantly have to consider and respond to the conditions in which their work is going to be seen. Which is kind of unique for a national theatre company. And these physical spaces – disused power stations, empty warehouses, abandoned garages, deserted drill halls, even actual theatres – that the National Theatre of Scotland has performed in are all (and always) remarkably fluid. A theatre space could literally be anything, be anywhere.

In 2017, the artistic programme of the National Theatre of Scotland is just as concerned with these things as the 2007 programme was.

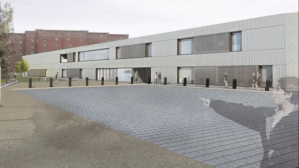

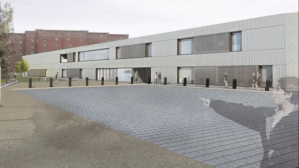

I’m not going to say much about Rockvilla, the amazing new building we’re gathered in. The building sort of speaks for itself. And what it can’t articulate, one of the architects responsible for it is here to give voice to that.

As for what goes on artistically at Rockvilla, who better to give you an insight than Simon Sharkey. As Learn Director, Simon has been a key member of the NTS artistic team since the very beginning. Who better to describe the creative forces that drive the great engine room of Scottish theatre, that have propelled it to enormous acclaim amongst audiences and participants at home and across the world.

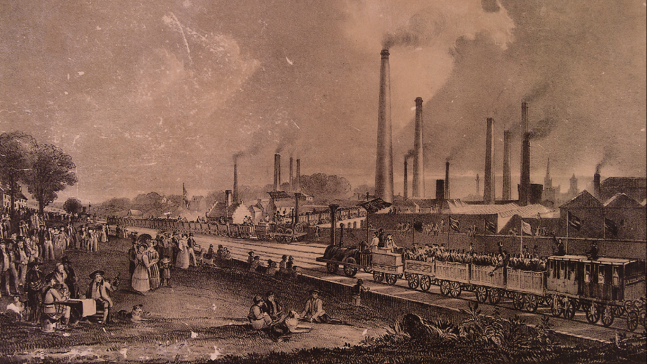

I use the phrase “engine room” deliberately, of course, given that we’re sitting by the Forth & Clyde Canal in an area synonymous with the heavy industry that grew the city’s fortunes in the 18th & 19th centuries. 150 years ago the place would have been throbbing with engine noise.

There’s always been a metaphorical “engine room” at NTS. Even when we were operating out of a couple of ramshackle offices in Atlantic Chambers at the bottom of Hope Street, different departments liked to think of themselves as the “engine room” of the organisation. These days, the website describes the whole of Rockvilla as the engine room. It’s also the name given to a new nationwide artist development programme.

What’s interesting, I think, is the appropriation of industrial terminology to describe cultural activity. In the face of the terminal decline of not just the heavy industries, but the electronic industries that grew up to replace them, we developed culture as an industry; indeed, the fastest growing parts of the economy are the “creative industries”.

But with that phrase, it’s as if we’re saying that industry itself wasn’t always creative. Some of the greatest creative minds our country has seen proved themselves – invented new processes, new technologies, transformed the world we live in – through the application of creativity and industry. And many of them hatched their ideas, made their fortunes right here, along the canal.

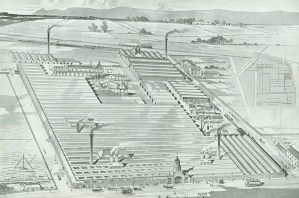

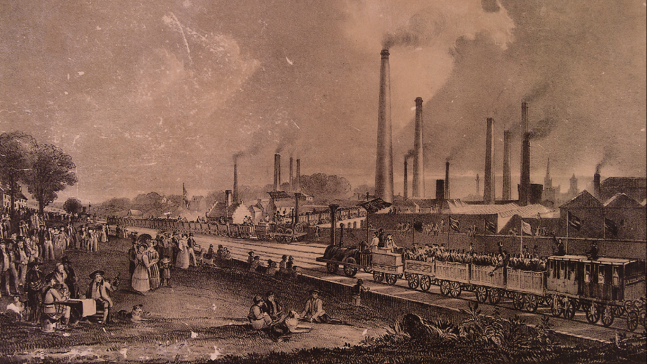

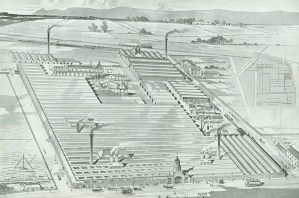

Like Charles Tennant, for example, who refined the bleaching process and whose chemical works in Springburn (pictured above) grew to become the largest in the world. Its chimney rose 130 meters into the sky above St Rollox, just half a mile away and was visible right across the city. If you could see through the smog, that is. Its chimney, known as the Tennent’s Stalk, was for a time the tallest in the world. His business partner was Charles Macintosh, whose name is synonymous still with fancy waterproof jackets.

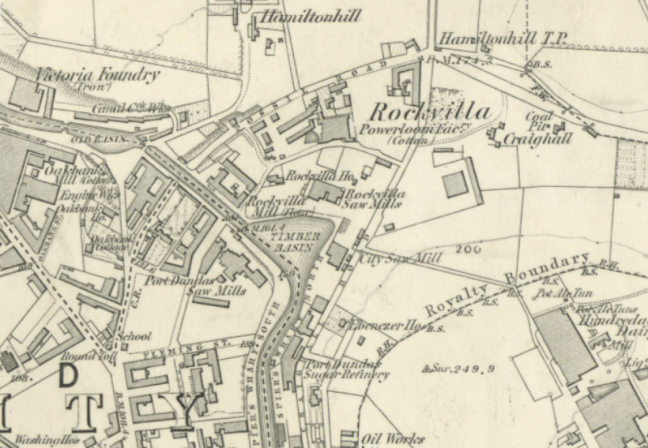

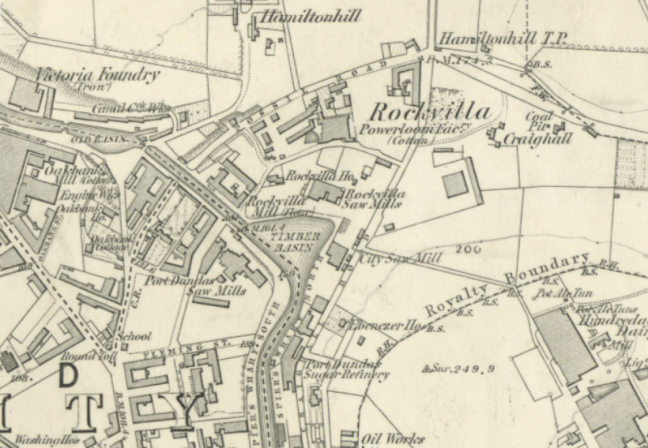

The whole area was a bit busier in its heyday, safe to say. A cursory glance at a couple of old maps tells us that within one square mile of where are standing, there would have been: saw mills, flour mills, gas works, glass works, brick works, pickle works, soap works, oil works, refineries, foundries, breweries, distilleries, power-looms, engine rooms, wharves, gantries, depots and sheds, horses and carts, boats and trains.

One. Square. Mile. Can you imagine?

Also within that same square mile, there were: parks and ponds, tenements, churches and ministries, wash-houses, poor houses, houses for the sick, cemeteries for the dead. The place was teeming.

Also noisy, smelly and dangerous.

Here’s the first Ordnance Survey map, surveyed around 1850.

Here’s the second edition, surveyed about 50 years later.

Rockvilla’s kind of a debatable name. No-one’s really sure where it came from. As we’ll see, there are lots of debatable names around the north of Glasgow. One reason Rockvilla was so called is possibly because large amounts of rock had to be blasted through to build the canal and to create the road that passes under it. The name was given to a house originally, then a sawmill, and a cotton mill, then a bit further up the road a church. Eventually it was given to this whole area here between Possil Road, Craighall Road and the Canal.

Rockvilla School was demolished in the 1990s and stood roughly where the Whisky Bond car park is now. You can still see traces of the building as you come up.

The project to create a new facility for the National Theatre of Scotland’s was set up under the auspices of the previous Artistic Director, Laurie Sansom. The decision to call it Rockvilla came about because of a desire to connect with the heritage of the site. Sansom liked it because, “It’s snappy and has a kind of cheeky irreverence.”

He said, “I really love the rock ’n’ roll name.”

Another possible reason Rockvilla got its name was because prior to it becoming a centre of industry, the area was full of quarries. Possil generally was full of quarries. And pits. Lots of pits. More of which later.

Here’s James Dorret’s map published in 1750. It’s not conclusive, but you get the idea.

Connecting new places with old names is of course exactly what we’ve been doing since the beginning of time. Glasgow’s rife with it.

To give you just one local example. Saracen Road and Saracen Cross just up the road take their name from the great Saracen Foundry built on the site of Possil House in 1860. They made all the cast iron stuff you associate with Victorian buildings – bandstands, fountains, railway station canopies, fancy public park railings, iron cemetery gates and the like – and they exported their products all over the world.

The owners, William Macfarlane Ltd, named their new foundry after the original location of their business at Saracen Lane in the Gallowgate, about three miles away. The Lane’s now gone but the name lives on in the Saracen Head pub, the original incarnation of which, famously visited by James Boswell and Samuel Johnson after their highland adventures, was on Saracen Lane. The Saracen foundry closed in 1965 but its legacy remains in the vast suburb of Possilpark, which was built to accommodate its workforce.

And nor is Rockvilla the first time the National Theatre of Scotland have chosen to pay homage to the heritage of a place in one of their buildings. The rehearsal room on Burns Street just down the hill on the other side of the canal was called The Glue Factory – because that’s exactly what it had once been. And the previous HQ – along the road – was named on the same basis, with a nod to the heritage of the building.

Here it is circa 1960.

In 2009, NTS outgrew its ramshackle suite of offices in Hope Street and moved into the Speirs Wharf neighbourhood, just as the area was developing into a bit of a melting pot for the creative industries. For seven years, the home of the National Theatre of Scotland was an old printers building called Civic House. Not quite as snappy as Rockvilla. Bit dull. Bit municipal. Very council. Not very NTS.

But the name preserves a link to the history of the Civic Press who operated from the building around the end of the 19th century into the 20th, right up until the 1970s.

They specialised in left-wing publishing and printing – election posters, leaflets and placards for demonstrations. Here’s a few of their publications.

![1 R UMAX PowerLook 2100XL V1.4 [3] 1 R UMAX PowerLook 2100XL V1.4 [3]](https://unshelf.files.wordpress.com/2018/02/tradeunions_civicpress.jpg?w=153&resize=153%2C240&h=240#038;h=240)

1 R UMAX PowerLook 2100XL V1.4 [3]

In 1969 they published a pamphlet by Emrys Hughes, married to Nan Hardie, daughter of Keir. It was called “The Prince, the Crown and the Cash” – reporting on the cost of the monarchy to the British public, specifically the prince of the title, Prince Charles.

It might not look much nowadays, but its white rendered brickwork with its numerous windows – installed to allow rows of typesetters to work in ample daylight – would have been quite the dish in its day. Set next to rows of traditional sandstone tenements, which were cleared in the 1960s, as they were being cleared all over the area to accommodate the new M8 motorway, Civic House would have seemed fresh and clean and modern.

Civic House is a survivor of radical political and cultural activity in the early to mid 20th century. Which turns out to be rather NTS after all – they couldn’t just take over any old printer’s building. Had to be a radical printers building. Appropriately enough, it’s now been taken over by a group called Agile City to be used as a creative learning space for progressive forms of city development.

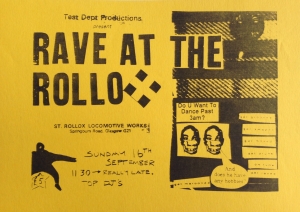

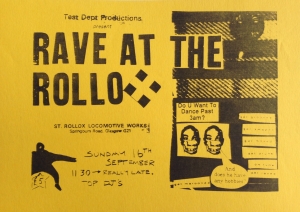

Talking of radical activity, I attended a performance during Glasgow’s 1990 City of Culture celebrations called The Second Coming.

It was set in of all places, the abandoned St Rollox locomotive works in Springburn, about half a mile from here. It was utterly extraordinary, one of the greatest performances I have ever experienced. It combined physical performance, music and text in a way I’d never seen before. Teams of boiler suited performers running full pelt with huge banners streaming behind them across a performing space maybe about a quarter of a mile long. Clanging live percussion played with metal tools on rusting railway sleepers and piles of old wheels. Massive bits of moving machinery rumbled ominously out of the gloom. Swinging cuboids of crushed railway steel crashed thrillingly into each other. All on a vast, vast scale. Literally, an industrial scale.

According to the programme notes, which I still have, “The need to find order, comfort, pride and purpose from the past is nowhere more apparent than in the meteoric growth of the heritage industry. It coincides with a nostalgia for a world which seemed stable and unchanging, unless it changed in Britain’s favour.”

The script by the journalist and writer Neal Ascherson concerned itself with a world where the heritage industry had taken over actual industry. People didn’t work in coal mines any more, they visited coal mining museums. People didn’t make steel any more, they made films about the steel industry. Everything was being absorbed into an endless self-referential feedback loop. It was written at the high water mark of Thatcher’s reign, shortly before she was ousted. But it could have been written today. These days our economy is largely a heritage economy.

The Second Coming was produced by Test Dept, whose Artistic Director Angus Farquar is still making extraordinary things happen in abandoned spaces with his organisation NVA which evolved from Test Dept in the 90s. Test Dept had made a name for themselves by turning unlikely industrial spaces into fertile creative territory. In many ways, NVA and Test Dept paved the way for the theatre without walls model adapted so successfully by NTS. They kind of wrote the book on it.

The space that was used for The Second Coming has long gone. It’s now, appropriately (or not), a massive Tesco. But the name of St Rollox still resonates. It certainly resonated with me when I was preparing this talk. I mean, it’s only down the road. Half a mile tops. So I’m thinking Rollox. Rockvilla. Could they be related? There’s also a school called St Roch’s in the area. Hmm… Roch’s. Rocks. The names are all a bit too similar to be a coincidence. Are they connected? Or is it just a load of old Rollox…

Well, it turns out they are! Well, at least a bit. St Roch was from Languedoc in the south of France, born in the 13th century. But how on earth did a medieval Occitane saint end up here? According to his entry in the dictionary of saints, he was patron of: plague, cholera, epidemics, skin diseases, skin rashes, knee problems, cattle, falsely accused people, invalids, surgeons, bachelors and tile makers. Which actually kind of makes him the perfect saint for the north of Glasgow. Right down to the tile makers.

A chapel dedicated to St Roch was built in 1506 near where Castle Street is now, in an area formerly known as Garngad, now Royston. After plague broke out later in the 16th century, victims camped in huts surrounding the chapel to pray to St Roch for healing. This then gave rise to a hospital and later a school dedicated to this French patron saint of the sick. (And the tile makers. Blessed be the tile makers.)

Curiously, there was a small loch slightly to the south of the chapel, known as St Roch’s Loch. Now. Try saying that together a few times when you’ve had a couple of drinks on a Saturday and you’ll see where we get the Scottish variation, Rollox.

The name Roch is apparently a Germanic name deriving from the word for rest – the connection with Rockvilla is probably circumstantial. As we saw earlier, the likely explanation for the name of this area comes from its origins in the quarry trade.

Rockvilla is situated in the ancient land of Possil, an estate which goes back into the furthest reaches of antiquity.

Here’s Roy’s Military survey of the lowlands from 1752.

And here’s the old Possil House, photographed by Thomas Annand, which was cleared to make way for the Saracen Foundry in the 1860s.

These days Possil is associated with the kinds of long term social deprivation that come hand in hand with long term industrial decline. For us Possil is a pretty negative word, rightly or wrongly synonymous with a range of specifically Glaswegian ills, from drug use to child poverty, third generation unemployment and low level crime.

But things are turning around. There’s a charity in the area called Possobilities, set up in 1984, running a variety of programmes to look after people in the Possil area. I love how they turn the name into a positive – but Possil is one of the oldest names in Scotland and in fact means “peaceful place”.

It comes from a variation of the Brittonic language, known as Cumbric, which was lingua franca round these parts until about the 11th century. It was spoken throughout the north of England to the southern lowlands of Scotland. It’s a bridging language between Welsh and Scots Gaelic, and it has given Glasgow a number of its place names – including the name Glasgow itself (which translates as “green hollow”). Other names that derive from Cumbric include Partick (“little grove”), Govan (“small hill”), Kelvin (“reed river”), Cathcart (“small wood on the River Cart”). The linguist Simon Taylor has done a lot of work on this, if you’re interested.

One can easily imagine pre-industrial Possil, as its Cumbric name suggested, as rather a peaceful place. It would be mostly tenant farmers, fields, cattle – and sheep. High Possil farm stood about a mile dead north of here, up Balmore Road, roughly where St Agnes’s church is now in the area known now as Lambhill. For three hundred years, the Lambhill Estate had been the seat of the Hutcheson family – the brothers George and Thomas who had established Hutchesons’ Grammar School and Hutcheson’s Hospital in Ingram Street.

Possil, as we’ve noted, was full of quarries, and an increasing number of pits yielding mostly ironstone and coal – about which more later. Then in April 1804, The Herald and Advertiser newspaper reported an event that quite seriously disrupted whatever peace was to be had.

“Three men at work in a field at Possil, about three miles north from Glasgow, in the forenoon of Thursday the 5th April. were alarmed with a singular noise, which continued, they say, for about two minutes, seeming to proceed from the south-east to the north-west. At first, it appeared to resemble four reports from the firing of cannon, afterwards, the sound of a bell, or rather of a gong, with a violently whizzing noise; and lastly they heard a sound, as if some hard body struck, with very great force the surface of the earth.”

It was a meteorite. The exact area it landed in was a quarry and, amazingly, for a massive rock from outer space landing in a pile of massive rocks, they managed to recover it. It was the first of four ever recovered in Scotland and only the second in Britain. It reportedly weighed several pounds initially but broke in two and the larger chunk was lost in the quarry rubble.

The rest has since been chopped and chipped, sliced and diced in the name of science, but a tiny fragment of the space rock remains on permanent display at the Hunterian Museum at Glasgow University. And don’t be fooled by the big commemorative stone on the far edge of Possil Marsh, should you ever venture round – it was located about a mile from the landing site because the council were afraid it would be vandalised by Possil locals…

The rest has since been chopped and chipped, sliced and diced in the name of science, but a tiny fragment of the space rock remains on permanent display at the Hunterian Museum at Glasgow University. And don’t be fooled by the big commemorative stone on the far edge of Possil Marsh, should you ever venture round – it was located about a mile from the landing site because the council were afraid it would be vandalised by Possil locals…

Since it’s Doors Open Day I should make a plug for Lambhill Stables. It’s run as a community hub and cafe, great place to stop in on a walk along the canal.

I was until recently Heritage Coordinator for a local history project in Lambhill called Coal, Cottages and Canals investigating the lost miners’ rows – or Raws – on the edge of the Possil and Kenmure estates. Mavis Valley, Laigh Possil, Kenmure and Lochfauld – which was nicknamed The Shangie.

These cottages sprang up with the advent of coal and ironstone mining operations around the north of Glasgow, around 1850, reaching their peak around 1890.

These are miners’ cottages we’re talking about, not yer granny’s heilan hame, or some cheesecloth n kailyard country but n’ ben affair. We’re talking no heating, no running water, no electric, no carpets, no shops.

These are miners’ cottages we’re talking about, not yer granny’s heilan hame, or some cheesecloth n kailyard country but n’ ben affair. We’re talking no heating, no running water, no electric, no carpets, no shops.

The cottages were built by the Carron Ironworks in Falkirk to house the miners in the nearby Cadder pits. They mined principally for ironstone to feed the foundries. What coal they dug up was of pretty poor quality and was mostly used domestically. The house came with the job – one of the most dangerous jobs there’s ever been – so if the breadwinner died, got sick or maimed, grew old, or got fired for smoking a fag where he shouldny – as happened more often than you’d think – the whole family were evicted and thrown to the mercy of the Parish or the Poor House. Unless you took a lodger. Or found a new husband.

With mining operations brought to a halt after the Cadder pit disaster of 1913, the rows went into steep decline and by the 1930s most of the families had packed up and left. In the cottages that remained, mostly in the better constructed houses of Mavis Valley, squatters took over, occupying them until the late 1950s.

There were a number of people I worked with on the project, one of them pictured here as a baby in front of Possil Row, who had personal associations with the rows. Many could trace their ancestry to one or more of the rows, some even remembered visiting them – especially the row at Lochfauld, known locally as the Shangie.

There were a number of people I worked with on the project, one of them pictured here as a baby in front of Possil Row, who had personal associations with the rows. Many could trace their ancestry to one or more of the rows, some even remembered visiting them – especially the row at Lochfauld, known locally as the Shangie.

No-one really knows why Lochfauld was nicknamed the Shangie. The place had a bit of a reputation for rumbustiousness – all the cottages had a bit of a reputation for rumbustiousness. The row opposite, for example, Kenmure Row, was nicknamed Mutton Raw after the theft of a sheep from a neighbouring farm and its subsequent butchering and distribution among the inhabitants brought collective shame and infamy to the row.

Legend has it that the Shangie was given the name because a passing sea captain, well-travelled, saw the state of the place from the bow of his barge and declared it reminded him of Shanghai.

Which apart from being a terrible slur on the good people of Shanghai, stretches the imagination somewhat to think that a shabby row of some forty odd cottages could resemble a bustling Far Eastern port city. A likelier explanation comes from the Scots language, where a shangie is a nuisance or troublemaker. It can also mean scraggy or gaunt. Both definitions could conceivably describe Lochfauld’s impoverished residents

Further along the canal, heading west past Maryhill, there’s another vanished neighbourhood with a mysterious local nickname: the Butney. You don’t find the Butney on maps, but everyone in Maryhill knows where it is. The Butney is formerly that triangle of streets around Bridge Street and Kelvin Street running up towards Maryhill Road. It’s called Skaethorn Street now, I think. Locals still know it as Butney Brae, with the canal lock flight and the old Kelvin Docks on the right. A new housing estate stands on the old Dawsholm Gasworks on the left.

Kelvin Dock, incidentally, is where the Clyde Puffer was born, at Swan’s Yard in 1856.

Until the puffer was invented, goods were transported on the canal by scows, 60 foot long barges 13 and a half feet wide, operated by two boatmen, a horse and a horseman. The Glasgow – Edinburgh Railway line had opened in 1842 and the canal was facing some serious competition. An engineer called James Milne acquired an iron-built scow and fitted it with a two-cylinder steam engine which made the distinctive “puffing” sound that gave the vessel its nickname and which gave rise to a whole genre of small cargo carrying ships which were to be the backbone of cargo transport on the canals and on the Clyde and proved to be “vital” links to the islands and communities along Scotland’s west coast for the next hundred years .

The Kelvin Dock’s still there. You can walk around the graving dock, which is more or less intact. Or do competitive extreme uphill swimming in the Red Bull Neptune’s Steps event that’s held there every year. Whether you’re tempted to go for a pint in the rum-looking Kelvin Dock pub on Maryhill Road, is entirely up to you.

Ask a local why the Butney was called the Butney and you’ll get the same salty sea captain confidence you get with the Shangie. Because it’s by Kelvin Dock, legend has it that’s where they loaded the prison ships to take the rank bad yins of the Parish to Botany Bay.

Botany. Butney. Obvious.

Except. Since the transportation of convicts to New South Wales ended in 1840, why would anyone load prisoners onto a horse drawn barge miles inland when all the big ocean going boats were being loaded on the Clyde at Broomielaw or Port Glasgow.

I spoke to a local historian who had spent twenty five years researching the area and he didn’t buy the Botany Bay banter either. His theory was that when the canal was being built, it attracted a certain kind of worker – the navigation engineers, navvies – who were billeted in lodgings around the dock. So maybe the Botany Bay thing came about because the hard-working, hard-drinking, hard-fighting men that built the canal were the type likely to end up in Botany Bay.

Someone else I met reckoned there was a pub or cafe in the area called the Botany Bay. But no-one can find any trace of it. And anyway, did the pub give the name to the area, or did the area give the name to the pub.

Another theory concerns the handloom factory by the Dalsholm Printworks. The section of the factory given to the removal of buttons from used fabrics was called – “the Buttony” . . .

A less debatable name is the “nolly”. A kind of kids’ nickname for the canal. Shangie. Butney. Nolly. Some great names up here. Happily, the etymology is easier with this one. You need to go full Glaswegian to get it. Canal. Canaul. Canaully. Nolly. Like rhyming off Latin declensions. Canal, canolly, canaul…

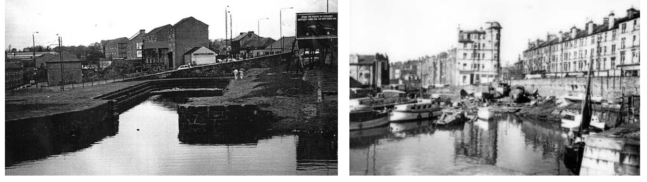

This is the Nolly Brig just by Firhill Stadium as it was in 1955. It’s a bascule bridge, a particular piece of canal infrastructure once almost ubiquitous across the network, sadly mostly all gone, that lifted up to let high masted boats through. Bascule’s a French word for a see-saw. The new concrete road bridge was built in 1990, and formalised the nolly nickname with an inscription carved in ’90s Glasgow Mackintoshy lettering on the underside.

The Canal was commissioned in 1763 and closed on 1st January 1963. The bits in between saw the rise and demise of Britain as an imperial power and the polishing and tarnishing of Glasgow’s crown as Second City of Empire. It’s important to recognise just how pivotal a role in all of that the canal was.

I mentioned the Carron Company earlier, who built the miners’ rows at Mavis Valley and Lochfauld. The ironstone mined there was transported by canal to the Carron foundries and used to make the cannons – the Carronades – that launched the artillery that crushed the colonies.

War is bound up with the story of the canal, inevitably. The Luftwaffe used the canal as a bombing run, following its glinting silvery moonlit path all the way into Clydebank.

There was a very real worry that the canal itself would be a bombing target during the Second World War, and a number of defensive gates or stoplocks were installed. If the Germans had scored a direct hit at, say, Possil Road aqueduct at Rockvilla, you’re looking at a serious amount of water flooding the city. The next nearest lock gate on the Edinburgh side from that point is 17 miles away at Wyndford.

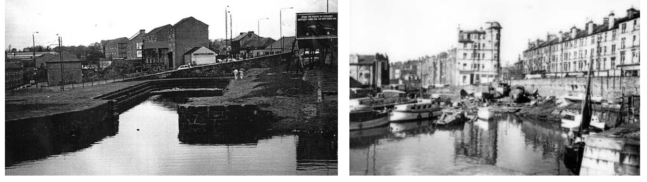

This is the stoplock at Stockingfield Junction, where the canal branches off in one direction towards Bowling and the Clyde estuary, and in the opposite direction in a three mile spur towards Port Dundas.

It’s called Port Dundas after Sir Lawrence Dundas, one of the major financial backers of the Great Canal and its first Governor. Glasgow city merchants were worried that a new port at Bowling would move the import-export trade on the Broomielaw many miles further downstream, bypassing the city entirely. They were eager to make sure the new canal came as close to the top of the town as possible, so paid for this extension.

A defensive stoplock was also installed at Speirs Wharf. Just in case. This picture’s from 2010.

The German bombers luckily never landed a direct hit on the canal. Some 60 years earlier, a group of Irish revolutionaries, known as the Skirmishers, led by Jeremiah O’Dononvan Rossa, who were devoted to the cause of Irish national liberation from British rule, had obviously identified the same destructive potential of a well-placed explosive on the canal. The Skirmishers trained men from Ireland, Scotland and England in the use of dynamite with the objective of seeking the “destruction of British life and property.”

On 20th January 1883, an off duty soldier called Adam Barr accidentally disturbed an explosive on the Possil Road aqueduct at Rockvilla. Had the bomb exploded, it would have flooded the city for 16 miles. The Skirmishers placed three bombs that night. One exploded in Tradeston, causing massive damage, knocking out street lighting across the city and creating a situation of mass panic and confusion. Less than an hour after that, a second exploded in in a disused coal shed at Buchanan Street train station, damaging windows and chimneys in nearby houses and busineses, luckily injuring no-one.

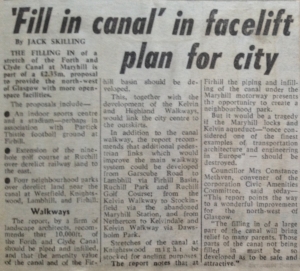

Arguably, the greatest peril the canals ever faced – and still face to an extent – is lack of use, irrelevance. Since the waterways closed in the 1960s there was much talk of the canal being filled in and converted to walkways and motorway – as happened with the Monklands Canal and the Paisley Canal. The stretch of the M8 that runs along from Cathedral Street past the Provan gasworks in the east end was built on canal infill.

Here’s some images of the canal being filled in in a more recreational way, pointing at a possible future for the canal. In 1850, the Rockvilla timber basin froze over and was used as a curling rink. In 2010, a group of dedicated fixed gear cycling enthusiasts ran a keirin championship on the ice.

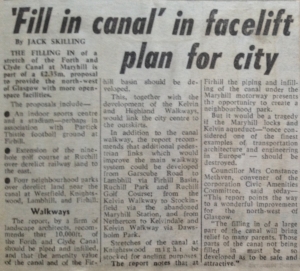

Here’s a clipping from 1972. The M8 was still a new fangled sign of the modern age. The Bruce Report, compiled in 1945 but still holding sway amongst city planners many years later, had recommended turning busy trunk roads like Maryhill Road and Springburn Road into motorway – which explains why Springburn is the schizophrenic deadzone you see today – a once vibrant community bifurcated by concrete canyons and speeding vehicles. Neighbourhoods separated from themselves.

Here’s a clipping from 1972. The M8 was still a new fangled sign of the modern age. The Bruce Report, compiled in 1945 but still holding sway amongst city planners many years later, had recommended turning busy trunk roads like Maryhill Road and Springburn Road into motorway – which explains why Springburn is the schizophrenic deadzone you see today – a once vibrant community bifurcated by concrete canyons and speeding vehicles. Neighbourhoods separated from themselves.

Maybe it was too expensive to build all these roads, maybe there were other better ideas out there. But the canals were saved by the work of a number of highly dedicated individuals and canal enthusiasts who worked tirelessly throughout the 1970s and 80s to keep them clean with a view to opening them again to boat traffic. And in 2000, they got their wish. The canal was reopened with £80m of public money. The Falkirk Wheel connected the Forth & Clyde with the Union.

The future of the canal as an inland waterway, like many of the names and places along its length, is debatable. Speaking purely from experience Scottish Canals are difficult and aggressive landlords, defensively territorial and, to be fair, being only partially funded by the Scottish Government, they need to make the canal work financially. It was ever thus: the canal was cut for commerce. But the result is that you don’t see many boats travelling through. You need to pay a crew to open the locks for you. Plus transit charges, navigation licenses. Mooring fees aren’t cheap either. The bill just for taking a boat across the 37 miles of canal from one side of the country to the other can run into hundreds of pounds. Also, given that there are 21 locks to navigate, it takes the best part of a day just to sail the first few miles of the canal from Bowling to Lambhill. As a functioning waterway, it’s just not very attractive for boat operators – though the Forth & Clyde Canal Society who run the big blue boats you see on Doors Open Day – the Voyager, the Gipsy Princess – will tell you their regular boat trips have never been more popular.

The most valuable parts of the canal you can’t monetise. It’s a vital part of the city’s green infrastructure. It provides safe walking and cycling routes away from heavy traffic. There are canoeing clubs. Cycling clubs. Extreme uphill swimming events. Swans and herons. Butterflies and damselflies. Stories galore.

But who ever made a buck out of telling stories?

I’m scouring my shelves for something that triggers a memory from my El Paso days. Something tangible – some souvenir or memento, a photo, maybe – that might act as a kind of emotional rope ladder that I can cast down to the sense reservoir that lurks deep down in the memory cave.

I’m scouring my shelves for something that triggers a memory from my El Paso days. Something tangible – some souvenir or memento, a photo, maybe – that might act as a kind of emotional rope ladder that I can cast down to the sense reservoir that lurks deep down in the memory cave. The strongest image I have of Carol and the one that stays with me as I write this, is of her face, beaming rosy and round and bright, dimpled at the cheeks, crinkled at the eyes. A smile of genuine warmth, of affection all-encompassing, unconditional. Gentle, easy, happy, a powerhouse of positivity. In my mind, she’s wearing a short-sleeved blouse and slacks, big glasses frame her eyes; her short wiry hair reminds me of my mum’s.

The strongest image I have of Carol and the one that stays with me as I write this, is of her face, beaming rosy and round and bright, dimpled at the cheeks, crinkled at the eyes. A smile of genuine warmth, of affection all-encompassing, unconditional. Gentle, easy, happy, a powerhouse of positivity. In my mind, she’s wearing a short-sleeved blouse and slacks, big glasses frame her eyes; her short wiry hair reminds me of my mum’s. And she was great at it. Carol’s house was a regular little united nations of French and Dutch and German and Japanese teenagers where we gathered for pool parties, pizza parties and Christmas parties to share our experiences and observations about life in Texas, our highs and lows, to gossip and moan, and above all to delight in the quirks and perks of our host city and its generous, colourful, beautiful, crazy people.

And she was great at it. Carol’s house was a regular little united nations of French and Dutch and German and Japanese teenagers where we gathered for pool parties, pizza parties and Christmas parties to share our experiences and observations about life in Texas, our highs and lows, to gossip and moan, and above all to delight in the quirks and perks of our host city and its generous, colourful, beautiful, crazy people. The world has shrunk a lot since 1987. Even more since the 1950s when YFU (Youth for Understanding) was set up. Its aim was, and still is, to foster peace and unity in the world through sharing values and experiences between cultures after the mass slaughter of the Second World War. Initially operating between Germany and the USA, school aged students travelled from one country to the other and lived for a year, learned the language and ways of life, and shared something of their own with the families who hosted them. The programme quickly spread to most of the rest of western Europe, Japan, China and other countries in east Asia, South America. The fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 opened up Eastern Europe, and now the list of participating countries runs to around 50 – the UK sadly but unsurprisingly no longer among them.

The world has shrunk a lot since 1987. Even more since the 1950s when YFU (Youth for Understanding) was set up. Its aim was, and still is, to foster peace and unity in the world through sharing values and experiences between cultures after the mass slaughter of the Second World War. Initially operating between Germany and the USA, school aged students travelled from one country to the other and lived for a year, learned the language and ways of life, and shared something of their own with the families who hosted them. The programme quickly spread to most of the rest of western Europe, Japan, China and other countries in east Asia, South America. The fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 opened up Eastern Europe, and now the list of participating countries runs to around 50 – the UK sadly but unsurprisingly no longer among them. I knew nothing of myself as a 15 year old. I knew even less about the world around me. Travel was a few summer trips to France and Tenerife with my parents, visits to uncles and aunties in England. The furthest I had ever gone on my own was a 15 mile bike ride in the countryside. At school, I was reasonably good at music, English, geography; hated maths, science. I was learning French but had never met a French person. I harboured vague notions of one day going to music college, but nothing definite, nothing you could call a career plan or a vocation.

I knew nothing of myself as a 15 year old. I knew even less about the world around me. Travel was a few summer trips to France and Tenerife with my parents, visits to uncles and aunties in England. The furthest I had ever gone on my own was a 15 mile bike ride in the countryside. At school, I was reasonably good at music, English, geography; hated maths, science. I was learning French but had never met a French person. I harboured vague notions of one day going to music college, but nothing definite, nothing you could call a career plan or a vocation.

never quite comfortable in my own skin. It is also part of the ‘me’ who continually has to go outside of himself, to lose himself, in order to find himself again; who permanently carries around a sense of displacement, of unbelonging – and ironically, my experience of going to school in the town I grew up in gave me that much more than travelling halfway across the world ever did.

never quite comfortable in my own skin. It is also part of the ‘me’ who continually has to go outside of himself, to lose himself, in order to find himself again; who permanently carries around a sense of displacement, of unbelonging – and ironically, my experience of going to school in the town I grew up in gave me that much more than travelling halfway across the world ever did.

![1 R UMAX PowerLook 2100XL V1.4 [3] 1 R UMAX PowerLook 2100XL V1.4 [3]](https://unshelf.files.wordpress.com/2018/02/tradeunions_civicpress.jpg?w=153&resize=153%2C240&h=240#038;h=240)

The rest has since been chopped and chipped, sliced and diced in the name of science, but a tiny fragment of the space rock remains on permanent display at the

The rest has since been chopped and chipped, sliced and diced in the name of science, but a tiny fragment of the space rock remains on permanent display at the  These are miners’ cottages we’re talking about, not yer granny’s heilan hame, or some cheesecloth n kailyard country but n’ ben affair. We’re talking no heating, no running water, no electric, no carpets, no shops.

These are miners’ cottages we’re talking about, not yer granny’s heilan hame, or some cheesecloth n kailyard country but n’ ben affair. We’re talking no heating, no running water, no electric, no carpets, no shops. There were a number of people I worked with on the project, one of them pictured here as a baby in front of Possil Row, who had personal associations with the rows. Many could trace their ancestry to one or more of the rows, some even remembered visiting them – especially the row at Lochfauld, known locally as the Shangie.

There were a number of people I worked with on the project, one of them pictured here as a baby in front of Possil Row, who had personal associations with the rows. Many could trace their ancestry to one or more of the rows, some even remembered visiting them – especially the row at Lochfauld, known locally as the Shangie.

Here’s a clipping from 1972. The M8 was still a new fangled sign of the modern age. The Bruce Report, compiled in 1945 but still holding sway amongst city planners many years later, had recommended turning busy trunk roads like Maryhill Road and Springburn Road into motorway – which explains why Springburn is the schizophrenic deadzone you see today – a once vibrant community bifurcated by concrete canyons and speeding vehicles. Neighbourhoods separated from themselves.

Here’s a clipping from 1972. The M8 was still a new fangled sign of the modern age. The Bruce Report, compiled in 1945 but still holding sway amongst city planners many years later, had recommended turning busy trunk roads like Maryhill Road and Springburn Road into motorway – which explains why Springburn is the schizophrenic deadzone you see today – a once vibrant community bifurcated by concrete canyons and speeding vehicles. Neighbourhoods separated from themselves.