Do I really need to read this book again?

Do I really need to read this book again?

Isn’t once enough? And haven’t I seen the movie like a dozen times? And aren’t they the same anyway?

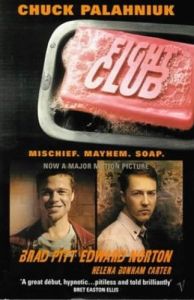

It’s not like it’s real literature, this stuff. Right? It’s pulp. It’s pop. With its movie poster cover of Brad Pitt and Ed Norton “in character” and that joke soap title device.

Did I ever learn to properly pronounce Palahniuk? “PAL-a-nuck”, I heard someone say on a podcast the other day. I always said “Pal-AN-yuk”.

Palahniuk said Fight Club “might be the most-quoted novel of the 20th century”. I wonder if he gets paid every time some op-ed writer or features hack or sub or anyone anywhere connected with putting words in print said “The first rule about ____ is you don’t talk about _____”

I wonder if he gets a royalty every time someone gets called a “snowflake”.

Obviously he doesn’t. Nobody makes any money out of writing any more, unless you’ve had a hit movie. But this shit has been in currency since the 90s – since the fucking 90s – which actually makes it a prime target for this blog since everything here seems to be about the 90s.

So, tell me why do I need to read this book again? And why now? What’s the point of reading anything?

I am Joe’s complete indifference.

I am 29 again. I’m living in Garnethill, a block and a half from the Art School and two from Sauchiehall Street, Glasgow’s answer to the Sunset Strip but slicked with piss and supper wrappers instead of palm trees and sunshine. All the glamour, glitz and debauchery you can shake a battered sausage at. The M8 motorway’s within easy earshot, but Garnethill is remote as an eagle’s eerie and feels like the Glasgow student rental market’s biggest best kept secret.

I watch the movie and I love it, as everybody does. I shoplift the book from my McJob (or more accurately, my Bargain Job) in a bookshop where I toil at the trough twice a week to provide beer stamps and food tokens to supplement the student loan that paid for the teacher training course which I am still – unbelievably – paying off at £2 a fucking week or whatever nearly 20 years later. I tear through the book in one or two sittings and somehow my shoplifted copy stays with me all that time until now, despite many flittings, lendings and charity shop culls.

Garnethill & Jordanhill. Mark & Jo. Val & Ali. Dom & Gordon. Claire & Johnny. Eastbank Academy & Duncanrig High.

In this world of dualities, we can’t forget our old pals, depression and anxiety, who announced their presence in my life that year, auguring the first indications of my having taken a massive misstep in life. My year of teacher training year ended with my first conversations about mental health with full-bore medical professionals. I’d sort of self-hypnotised myself about going into teaching and it wasn’t going well. Standing at the platform edge at Shettleston station fantasising darkly about potential ways out was a particular low point. I was in massive denial about everything. Why was I putting myself through this? Maybe I was doing it to please my mother. Maybe I was doing it to please my father. Maybe I’d convinced myself I needed to have a profession, a vocation, a title, something – metaphorical or literal – that I could hang around my neck to define me in some way, to create substance and structure out of the slime that I surely was.

And maybe that’s what depression is. Your own personal Tyler Durden rearing up inside and kicking the absolute shit out of you. Or trying to knock sense into you.

I am the all-singing, all-dancing crap of the world.

Reading the book again, depression is, on some level, one of the things that Fight Club seems to be about. I have to say “on some level”, of course, because Fight Club has more levels than a New York City skyscraper. It’s “about” a lot of things, but depression is surely in there. All that stuff about hitting bottom? And I mean, what’s this if not a perfect literary evocation of the blackness of depression:

I wanted to breathe smoke. Birds and deer are a silly luxury, and all the fish should be floating. I wanted to burn the Louvre. I’d do the Elgin Marbles with a sledgehammer and wipe my ass with the Mona Lisa. This is my world now.

But don’t go looking for answers, because on another of those levels Fight Club is like some kind of anti-self help book:

Maybe self-improvement isn’t the answer. Maybe self-destruction is the answer . . .

Maybe we have to break everything to make something better of ourselves . . .

It’s only after you’ve lost everything, that you’re free to do anything . . .

I should run from self-improvement and should be running towards disaster . . .

On some other level – quite a few of them, actually – it’s a how-to manual, like the Anarchists’ Cookbook wrapped up inside a day-glo narrative. Fight Club cheerfully primes its readers on the basics of a number of anarchist staples, such as how to make napalm, or nitroglycerine, or plastic explosive, or how to make a silencer for a gun. If you’re paying attention you can even learn how to topple a building, or at the very least how to blow up your own apartment.

Some of the more socially acceptable “tips” include how to be a cinema projectionist, how to run an allotment, and how to make soap. (First we render fat.) On the whole, you could say that Fight Club instructively demonstrates effective multitasking – up to a point, anyway.

On another level again, perhaps in a building all its own, Fight Club can be read as a philosophical treatise on the crisis of masculinity. That’s well-enough elaborated on elsewhere but it’s really interesting looking back at how tame and simplistic this notion seems with everything that’s going on right now regarding the debate around gender fluidity and the increasingly strident noises made on the radical left where even discussion of biological gender is considered hate speech. In this context, masculinity has it easy.

But how does Fight Club work as a novel?

My first reaction on re-reading it is that the language in this book is one of the reasons why novels – and novelists – continue to exist at all. You can’t write a how-to book or a self-help book or a philosophical treatise with this kind of language. No-one talks like this. No-one else really even writes like this. The only home for this kind of language is in a novel. It’s intrinsically literary.

It’s playful, but not self-consciously so. It’s exuberant, but not tiresomely so. It takes joy in its unusualness, but not at the expense of story and character, but in service equally of both.

And it’s not just the words. There’s the constant timeline fuckery. The jump-cut syntax and channel-hopping narrative are instinctive and familiar and hugely entertaining. That “twist”, hidden in plain sight from the very first line. The character definition and narrative voice are so beautifully honed, no wonder this book struck a chord that still reverberates.

But it’s the language, the searing, soaring language that keeps me gripped, image after lacerating image. It’s punchy enough to snap a tooth off at the root, you could say.

The text is jam packed with verbs, the muscle and sinew of literature. This book is all go, all do. In Fight Club verbs do the work of adjectives. What he sees, we see. But you see what’s happening, first and foremost, not just pages and pages of costume and scenery. There’s a total lack of adverbial phrases, or static paragraphs bloated with description. Like you read a book like this to know what colour the wallpaper is. The fetching red leather jacket that Tyler Durden wears in the film is nowhere in this book. The bits of description that do exist are there to underscore the violence and darkness at the heart of the narrator’s world.

It’s all very Elmore Leonard in this respect, but the novel it reminds me of most here is American Psycho, a book every bit as brutal as Fight Club, but which uses language in a very different way. Brett Easton Ellis distances you with endless descriptions and lists of brand names. These descriptions point to the vacuity of his narrator Patrick Bateman and highlight his obsession with surface and status, as represented by Bill Blass shirts and silk-screened Armani ties. You don’t see the person he’s describing so much as you see a walking till receipt.

In Fight Club you see everything you need to, but you also feel. A lot. Mostly pain.

Last week, I tapped a guy and he and I got on the list for a fight. The guy must have had a bad week, got both of my arms behind my head in a full nelson and rammed my face into the concrete floor until my teeth bit open the inside of my cheek and my eye was swollen shut and was bleeding, and after I said, stop, I could look down and there was a print of half my face in blood on the floor.

And what do we get at the end of it all? After all this fighting, all this violence and mayhem? Well, his narrator gets the girl, for one, which puts it right up there with all the fairy tale endings that have ever been, and strikes an oddly conservative note for a novel with such radical content. Is Fight Club then a sort of fairy tale? A parable for our times about the redemptive powers of love?

This isn’t love as in caring. This is about property as in ownership.

Possibly not.

Apart from that, though, and different from the movie, there are no explosions, no end of the credit system, no collapsing buildings, no collapse of the world order. No nothing. Which is a closure of sorts, and in a funny kind of 90s kind of way, the end of the book reminds me a bit of the Seinfeld credo.

I’ve met God across his long walnut desk with his diplomas hanging on the wall behind him, and God asks me, “Why?”

Didn’t I realise that each of us is a sacred, unique snowflake of special unique specialness?

Can’t I see how we’re all manifestations of love?

I look at God behind his desk, taking notes on a pad, but God’s got this all wrong.

We are not special.

We are not crap or trash, either.

We just are.

We just are, and what happens just happens.

And God says, “No, that’s not right.”

Yeah. Well. Whatever. You can’t teach God anything.

It conjures all the wrong things for me.

It conjures all the wrong things for me. Ok. ‘Hate’ might be too strong a word for it. But it’s up there with once-useful words like ‘narrative’ and ‘curate’ and ‘bespoke’ that have been worn to the knuckle from over-use by slack-thinking newspaper columnists and advertisers to describe every kind of human experience, from buying a loaf to falling in love, from getting dressed to dying of cancer.

Ok. ‘Hate’ might be too strong a word for it. But it’s up there with once-useful words like ‘narrative’ and ‘curate’ and ‘bespoke’ that have been worn to the knuckle from over-use by slack-thinking newspaper columnists and advertisers to describe every kind of human experience, from buying a loaf to falling in love, from getting dressed to dying of cancer.

Anyway, the best adventures seem to happen to other people. To heroes. To characters. The larger than life sociopaths in fancy dress with brandable first names who populate our popular culture. Sherlock. Tintin. Tarzan. Alice.

Anyway, the best adventures seem to happen to other people. To heroes. To characters. The larger than life sociopaths in fancy dress with brandable first names who populate our popular culture. Sherlock. Tintin. Tarzan. Alice.