Dir: Gary Nelson (1979)

With Robert Forster, Anthony Perkins, Ernest Borgnine, Maximilian Schell et al

Sometimes a piece of art, a movie, a book, music, reaches you at exactly the right time, the right age.

The Black Hole came out in 1979 when I was 8 years old and it captured my imagination like nothing else. I saw it that summer with my best friend from round the corner, David. He was a bit older than me but we were completely on the same wavelength. We enjoyed the same stuff and we played brilliantly together. It was the first time I had gone to the cinema on my own, or at least without a grown up. The film possessed us completely. We took forever to walk home afterwards. It felt that we had to act out every one of our favourite scenes, channelling the moves, the mannerisms and the spirits of our favourite characters.

Star Wars had come out two years earlier, when I was just a bit too young for it. My Nana took us to see Star Wars on the vast screen at the old Kelburne Cinema in Paisley one rainy day in the summer holidays. My brother, a toddler at the time, had fallen asleep during the matinee and Nana didn’t want to wake him, so we stayed put and sat and watched it all over again. I enjoyed the film, but it didn’t resonate with me the way The Black Hole did.

One criticism you can make endlessly about The Black Hole – it’s no Star Wars. In the first three minutes of Star Wars alone, there’s more action than in the first twenty of The Black Hole, maybe even the whole film. There are many obvious comparisons between the two movies – they are both set in outer space with laser guns and cute robots. And while there is more than a hint of bandwagon jumping in the latter film, they are fundamentally different movies, arguably even different genres – if Star Wars is a space western, The Black Hole is more . . . space gothic horror. But more about that in a bit.

I didn’t care about any of that back then. I loved everything about The Black Hole. I had the original soundtrack LP, which Nana won in one of the competitions she was always entering. I bought Alan Dean Foster’s novelisation with summer holiday pocket money and read it many times (which possibly helped to fill out a lot of the plot holes and inconsistencies I can see now in the movie). And somewhere on my shelf I have the DVD version, bought on impulse in Fopp one rainy day ten or so years ago. I threw out my dodgy old DVD player so right now I’m streaming the film on Disney+ from my laptop. Does anyone even have stuff on shelves any more?

Sometimes it’s better not to interrogate the reasons for returning to a particular text or piece of art, sometimes the reason reveals itself as you write and reflect. I’m not quite sure why I’m watching this film now. I haven’t written anything for months, most of the year in fact, since the start of the coronavirus crisis, with lockdown and all the anxiety and uncertainty it has brought into our lives. I realise as I start to write that words are trickier propositions now after so many months away from using them to organise my thoughts. They don’t come as easily. My line of thought is too easily broken. It makes me aware that my internal life has been increasingly dominated by imagistic sense impressions, emotions, all of it vague and unarticulated. Nothing seems clear anymore. It’s been a weird year.

Maybe I just want to be spirited away to the far edges of the universe. I want to feel totally immersed in that world again, as I did when I first saw it because it’s deep into 2020 and I’m in the mood for some escapism. I’m ready to descend into some kind of fantasy void.

The Disney+ version starts with an “overture”: two and a half minutes of John Barry’s main theme over a blank black screen. (Way to get the kids engaged, Disney!) I have always been a fan of Barry’s music – his ear for a great tune, his swooning harmonies, his love of a strident french horn – and I have always loved this soundtrack because it’s a pure nostalgic hyperlink to that summer and the first time seeing the film. Listening to it now, however, over that black screen, I find the music oddly jarring. It’s a kind of military march, imperious and bombastic, like it’s setting the scene to a film about Americans in WWII. The black screen overture gives way to the opening title sequence and another grand theme from Barry, this time an eerie, spiralling waltz. I can hear flashes of Strauss (Richard) and Mahler in the orchestration, maybe; some zingy synth work distantly recalls Messiaen’s Turangalila Symphony. But really it’s all a bit of a plod: a stately adagio compared to the sparky andante of John Williams’s brassy Star Wars opener.

Watching it’s a bit of a plod, too, I’ll be honest. I want to love the film as much as I did back then but it’s a hard movie to stick with. There’s a lot of expository dialogue, religiousy wiffle-waffle, wibbly-wobbly sci-chat, portentous philosophical doomchat. The movie finally begins with a robotic voice incanting this nonsense:

2130; day 547. Unscheduled course correction due at 2200. Pre-correction check: rotation axis plus three degrees. Nitrous oxide pressure: 4100 rising to 5,000. Quad jet C and D on pre-select. Rotor ignition sequence beginning in 3-0. Thruster line reactors on standby.

The voice belongs to V.I.N.CENT, a floating puppy-eyed robot whose name stands for “Vital Information Necessary Centralised”. V.I.N.CENT is very obviously a cuddly C-3PO/ R2-D2 hybrid but doesn’t quite have the charisma of either. As a boy, I absolutely adored V.I.N.CENT. I sort of wished I could have him for a pet, to teach me interesting things, to stand up for me and fight my battles. For my birthday that year, I was given model kits of him and his evil robot nemesis, the silent, glowering Maximilian.

Where Maximilian is a mute maroon hulk, V.I.N.CENT is endlessly rattling off folksy aphorisms and improving epithets. He variously quotes Greek philosophers, Arabic proverbs and American Civil War Admiral David Farragut (“Damn the torpedoes! Full speed ahead!”), amongst others.

“Are you put on this ship to bug me, V.I.N.CENT?” asks one of the humans. “No,” V.I.N.CENT replies. “To educate you.”

I had rather enjoyed V.I.N.CENT’s capacity for smart sounding bits of wisdom, whereas now it seems laboured and just slows everything down. If there’s any education going on in this movie, it is certainly not of the scientific kind. For all the talk of anti-gravity bubbles and event horizons, “the science” on display is as wonky as the dodgy greenscreen backgrounds. The film was famously derided by celebrity astrophysicist Neil de Grasse Tyson as one of worst movies ever made, one which “didn’t get any of the interesting science about black holes right”.

It’s not a perfect movie by any means; a lot of things just don’t stack up. But it seems almost churlish to pick holes in The Black Hole like that. Movies get stuff wrong all the time. History movies get history wrong. Biopics get biographies wrong. Comedies fail to make you laugh.

The fact is that black hole in The Black Hole isn’t really a black hole, not in the astrophysical sense, but rather in the metaphysical sense. As a cinematic presence, there is no questioning the hole’s awesome aura. From the giant glazed ceilings of the control tower of the USS Cygnus, it lurks like a cosmic maelstrom, drawing stars into its swirling cerulean vortex. Is that what black holes really look like? Does it really matter? There’s something irresistible, something undeniably beautiful about it and you kind of get why crazy Max Reinhardt is obsessed by it and wants to launch himself into the centre of it. Who wouldn’t?

Watching again, I’m struck by the range of references to other texts. For a sci-fi kids’ flick, it’s surprisingly literary. Dante’s Inferno gets a name-check within the first five minutes. V.I.N.CENT quotes Cicero. Reinhardt quotes from the Book of Genesis. There is something of Poe’s Descent into the Maelstrom in its Gothic mood and the mariner’s obsession with a whirling void. Milton isn’t quoted directly but his vision of Hell is all over this movie, especially in the final “Heaven and Hell” sequence as the characters spiral off on divergent paths at the black hole’s event horizon.

Its literariness is a distraction, though, and not central to the business of the movie which is . . . what, exactly? What’s the film really about? What on earth, you ask yourself, is going on?

What’s going on, for example, with Old B.O.B.? What’s with the sad eyes and Texas accent? And what’s with the acronym? His name, he tells us, stands for “Bio-sanitation Battalion”, which isn’t even a proper acronym. It’s details like this, like the gratuitous intertextuality, that bring me right out of the drama. For Neil De Grasse Tyson it’s bad science. For others it might be bad acting or bad set design or continuity gaffes. For me it’s stupid acronyms. Why did the writers give them these ridiculous tortured names? And while we’re at it… robot/ human ESP? Robot pubs? That ending? There’s a lot to unhook you from the story, here.

Old B.O.B., though, may hold the key to the mystery of the movie’s Big Theme, or its controlling idea. It’s not a heroic quest, not a whodunnit, not a ghost story or a horror or any kind of good vs evil thing. It’s something else.

“This is a death ship,” says B.O.B.

And sure enough, death is everywhere in this movie. The robot funeral that Captain Holland witnesses. The walking dead of the Cygnus’s “crew”. Dr Kate’s dead dad. The death of Anthony Perkins’s character, Dr Alex Durant, at the hands/ blades of mad Maximilian. Harry’s own self-inflicted death during his bungled escape. The script references death all the time. It’s the great Disney death movie in space.

“Death is the point of all our searching”, this movie seems to say. “Death, the ultimate prize”. At one point, in a line almost thrown into the void so casually and with such little moment is it uttered, Reinhardt seemingly invokes St. Thomas Aquinas when he says, “Some cause must have created all this . . .” gesturing out towards the black hole. “But what caused that cause?”

Perhaps Reinhardt believes he will, within the black hole – “In, through and beyond!” – find proof of the existence of God. Perhaps, in some ways, The Black Hole is a quest story after all. As Reinhardt says, the prize of sailing his ship into the black hole is, “The possibility to possess the great truth of the unknown.” Is this a quest for death-in-life, a quest for immortality?

The tragic irony here is of course that, as B.O.B. explains, “The most valuable thing in the universe, intelligent life, means nothing to Dr. Reinhardt.” It is this, rather than his belief in Thomas Aquinas’s “first cause” philosophical proof of God, which ultimately dooms him, in the closing section of the movie, to burn in a Hell of his own making. As the characters pass through the black hole, Reinhardt becomes weirdly subsumed by the dark Satanic mass of Maximilian, his eyes flickering in terror from behind the robot’s visor as machine and man roast upon a craggy rock amidst a raging inferno, as the cloaked figures of the Cygnus’s undead crew file below them towards the flames. A robot hell designed by Milton.

It would be terrifying if it wasn’t all so perplexing. You also have to wonder how a film about such existential matters ended up with cuddly robots and laser battles. Is it even a space movie?

But why am I watching this nonsense? Why am I giving it the time of day?

Maybe there’s that feeling of being tethered to the edge of the abyss that the coronavirus pandemic has allowed to grow in our locked-down lives. Maybe there’s nothing to look towards except our own oblivion. I can feel my own mind starting to splinter, as the gravitational pull of the void asserts its hold. What am I looking for? Or have I in fact stopped looking?

I’m taking far too long (again) to find the point of this. My insomnia returns with a vengeance as November grows long and the days grow short. Events pile up. America has gone mad, schisming into a heaven/ hell of its own making. We try to buy a new house. The world beyond our windows seems to shrink as lockdowns return across the country. The virus seems to be circling around us. I begin a brief period of self-isolation, due to a contact at work testing positive, but I’m fine and staying in doesn’t seem any different to the way the rest of the year has gone.

And then, one night, wrestling with insomnia, I make the connection, about my need to revisit my imaginative wanderings in space. At some point earlier in the year, I had started doing a guided meditation with my daughter at bedtime. It was based on the idea of what you see when you close your eyes. Those swirling shapes and blocks of blurry colour that float behind your eyelids, and the imprint of your retina that you can still see distantly as a black circle through it all.

We called it The Big Black Dot.

www.sketchybeaststudio.com

Every night for four or five months after stories, cuddled up cosy in bed, I would take her through the inner space of her imagination, in search of the big black dot. It was far away at first, gradually drawing closer as we floated and drifted through the fuzzy red stars and blurry blocks of green and orange and purple. Up and over the the rainbow bridge, into darkest space, the big black dot loomed like a planet. As we drew closer still, its edges became clearer. Was it really a planet? Or was it a window you can look through? A door you can walk through? A pool of water you can dive into? A fluffy carpet you can lie on?

And as we hung in space, the big black dot moved gradually beneath us. We let go of whatever we were holding on to and fell, down down down, and landed softly on the surface of the big black dot. It held us there, safe and comfortable, looking up at the stars we had been floating in only moments before. And as we looked up, there, in the sky just above us, would be . . . another big black dot, shiny this time, like a giant eye gazing down on us. And we would see ourselves, reflected in the shining surface of the big black dot, stretched out, relaxed and happy, looking up.

And we see the eye blink. Once. Then again. Until finally it closes and we fall into a deep, deep sleep. . .

I am reminded that I had big plans this year to do more writing, in a serious and committed way. I had plans to attend a writing retreat with the Arvon Foundation, to edit the many stories I had written for my daughter, to commission artwork for them and to work towards finding an outlet for them. Maybe even a publisher. Of course, none of this has happened.

The artwork, above, with the Big Black Dot lettering, was an attempt at this, belatedly, to try and put this “story” into a book for my daughter. But like many other plans this year has disappeared into the void, sucked up – in, through and beyond – into god knows where.

The Black Hole suffers from its portentous over-working of a giant metaphor that’s almost too big and to vague to really do anything with. The Big Black Dot is something else. It’s not a metaphor for anything. And in writing this it makes me think that somewhere, dimly, on the event horizon of the soul-sucking maelstrom that has been the year 2020, there is the glimmer of a life beyond the darkness.

Do I really need to read this book again?

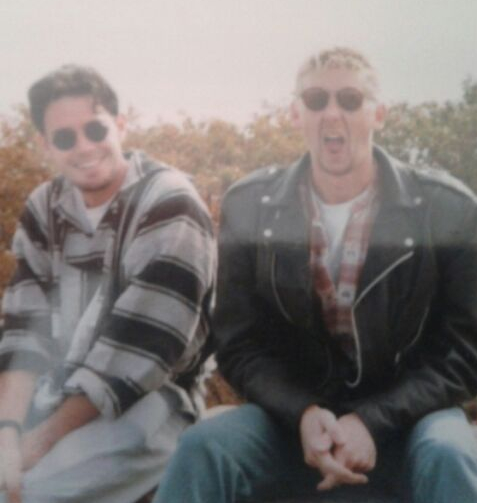

Do I really need to read this book again? You don’t know it, my friend, but you kind of showed me that. Not just for me but for countless others who knew you and loved you. You had an amazing talent for looking after people. You even made a living out of caring.

You don’t know it, my friend, but you kind of showed me that. Not just for me but for countless others who knew you and loved you. You had an amazing talent for looking after people. You even made a living out of caring. You had my name listed as “Sax” in your phone (was that the joke? “Sax in ma phone”?) which made me laugh, even though I haven’t played the thing in earnest in years. For me, Russ, you were all about the bass.

You had my name listed as “Sax” in your phone (was that the joke? “Sax in ma phone”?) which made me laugh, even though I haven’t played the thing in earnest in years. For me, Russ, you were all about the bass. Supertramp

Supertramp

Shooting Rubber Bands at the Stars

Shooting Rubber Bands at the Stars Queen

Queen

Ritual de lo habitual

Ritual de lo habitual Varmints

Varmints The Anna Meredith thing was so typical of you in so many ways. You were so open to new and interesting stuff. For every Rush or Bryan May gig we went to, there was an equivalent Ornette Coleman & Prime Time or John Zorn. And as much as you loved big bombastic cockrock, you could be just as passionate about female artists – Joni Mitchell, Ricky Lee Jones, Tracy Chapman, Oleta Adams, Aimee Mann.

The Anna Meredith thing was so typical of you in so many ways. You were so open to new and interesting stuff. For every Rush or Bryan May gig we went to, there was an equivalent Ornette Coleman & Prime Time or John Zorn. And as much as you loved big bombastic cockrock, you could be just as passionate about female artists – Joni Mitchell, Ricky Lee Jones, Tracy Chapman, Oleta Adams, Aimee Mann.