Dave Henderson, my uncle, was a legend. No other word for it.

Dave Henderson, my uncle, was a legend. No other word for it.

To me, growing up, he was this larger-than-life superhero figure, like Jacques Cousteau or James Bond. I even thought the guy in the Milk Tray ads that were out at the time had a slight air of Uncle Dave about him. There was just no-one else in my life who even remotely resembled him. And though the mystery that surrounded him gradually diminished the more I got to know him, my respect and admiration for him never did.

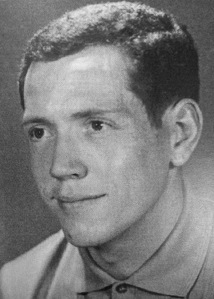

He passed away recently, at the legendary age of 80. I thought he’d live to a hundred. I remember him as a singularly athletic man. He was lean and wiry with the sort of relaxed physicality and poised energy that came from years of military discipline, someone used to being ‘at ease’. I remember playing in my Nana’s garden with Dave and all the cousins. A ball got bounced into the busy main road and Dave, to our astonishment, leapt over the hedge in a single bound to rescue it. It was only a hedge, but for us it was like he’d jumped over a tree.

He lived quite far from us, so we saw him only occasionally. My mum, Dave’s wee sister, told us he had settled in the south of England to get as far from their mother as it was possible to be while still living in the same country.

I don’t know how true that was but Annie, our beloved Nana, was a strong-willed woman with high expectations of her children. Dave, coming of age in the late fifties, early sixties and possessed of a will every bit as strong as his mother’s, had a fresh set of inclinations and modern ambitions that were in fierce opposition to the stern Catholic mores of his elders.

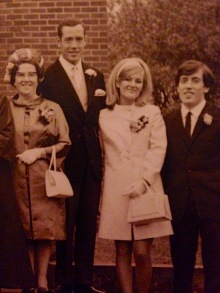

They clashed frequently and, as soon as he could, Dave took flight. Literally. His ticket out of Glasgow was the RAF. He joined the military band and travelled the world, eventually settling in Portsmouth where he trained as a telecommunications engineer and married his sweetheart, my wonderful Aunt Jan.

I only ever heard about Dave’s early conflicts with Annie in a roundabout way, alluded to in passing and quickly glossed. Sometimes you picked it up in a roll of Dave’s eyes when she was mentioned. My mother occasionally hinted at Annie’s strict and demanding nature, but never went into any detail. Age had evidently mellowed her – Nana was nice as ninepence to my brother and I and all our cousins, to the point of spoiling us. Annie was as sharp as a tack and possessed a wicked sense of humour. Brilliant at cards. An amazing wordsmith. She could be cunning but never malicious, and a wiser, more generous, more loving person I have never known.

Dave featured large in the tales that Annie and Auntie Maxie used to tell about the two sides of the family, the Hendersons and McArthurs. They loved to conjure the world they grew up in over endless pots of tea and rounds of toast in front of the ‘living flame’ gas fire in their living room. It was a beautiful little cosmos, lively with characters who all seemed to be called Tim and John and Martin. It was in their telling that Dave became this mythical hero of lore. A legend. An actual legend. And the fact that we saw him so seldom allowed the legend to grow.

We heard about the time Dave performed in the Edinburgh Military Tattoo. They described how Dave marched out with the RAF band onto the Edinburgh Castle Esplanade and, without missing a beat or breaking stride, waved up directly at them. It seemed so improbable to them that he should be able to pick them out in such a big crowd, but to hear Dave tell the story years later, Annie and Maxie wrapped up against the dimming northern night in their tartan blankets and rain-mates cut rather a conspicuous figure amongst the tourists.

There was Dave the deep-sea diver. He’d got into scuba during his years in Singapore and the far east. When he returned to civvy street and was living on the south coast of England, he was part of the dive team that did some of the reconnaissance work on Henry VIII’s sunken warship, the Mary Rose, before it was raised from its 450 year old bed in the Solent. Apparently, Dave’s local scuba club knew all about the wreck of the Mary Rose and had been diving it for years before there was talk of raising it. We watched him being interviewed on the news one day in his wet suit and diving gear. Legend status assured.

He and Jan lived for a while in the tiny town of Selsey, stuck on the tip of England that pokes into the Channel known as the Manhood Peninsula. Television’s Patrick Moore was their starry neighbour. My only memory is of a house filled with mysterious artefacts – strange looking shells, bells, ship’s wheels and assorted treasures from the deep, many of which he’d personally recovered. Their house was the first time I’d ever seen tropical fish and I’d stand at the massive tank, soothed by the sound of bubbles and mesmerised by the darting neon tetras and the languid swooshing angel fish.

There was Dave the jazzer. Nana had an album filled with fabulous photos of Dave from his military days, pictured in various far-flung locales. He played alto sax in the RAF dance band who had a regular gig at a hotel out in Singapore. He also had a jazz combo that jammed after hours in a kind of West Coast cool/ Paul Desmond/ Dave Brubeck vibe. Dave’s instrument was a super-stylish white plastic Grafton alto sax – one of the classic saxophone makes of the 50s, made famous by the likes of Ornette Coleman, Charlie Parker and Johnny Dankworth. In one of the photos, there’s Dave and his band with Buddy Rich – one of the greatest jazz drummers of all time. He was on tour, passing through, and came to sit in on one of Dave’s jams. Absolutely legendary.

No surprise, then, that I became a sax player. After my very first school music class at high school, I impressed my teacher enough for him to offer me an instrument to learn at home. I chose the trumpet. I came home excitedly that night and showed it to my mum. She didn’t much like the idea of an apprentice trumpeter in the house and I was sent back with it the next day with the explicit instruction to ask for something quieter, a “nice gentle instrument” like a flute or a clarinet “like your Uncle Dave plays”.

That clarinet took me into the military too, years later, as a bandsman in the 51st Highland Volunteers (the Black Watch Territorial Army band, based in Perth – which is a whole other story). I played first clarinet there for five years and the money I made allowed me to travel extensively throughout Europe in my early 20s and even paid for my first saxophone. I didn’t quite get to see the world with the TA, but it took me to some interesting places with some weird people and the music was never less than glorious.

I loved how musical Dave was. My Dad and I went down to Portsmouth to visit him and Aunt Jan. It was not long after his younger brother, my uncle Tom, had passed away, and the same year my daughter was born. During our stay, Dave took me up to his music room in the attic. He’d long since parted company with that gorgeous Grafton alto, but there was his clarinet which still sounded silky warm and woody, even in my unpractised hands. And there was the old diatonic button accordion that had belonged to his father, Hugh, my grandfather. There was a banjo ukelele that he’d had since he was a boy, given to him by an old aunt. And there was his newest addition – an electric guitar. At the age of 74 he had decided to learn and was teaching himself with YouTube and a Tune-a-Day book. He was just inspirational.

We didn’t keep in touch so well between visits. A few emails now and again, but I found it hard to sustain any kind of correspondence. Dave was always much better at that sort of thing. For years he phoned Annie every Friday to check in, swap stories, exchange news. And he continued this tradition with Maxie long after Annie died, calling her every week at the appointed hour until she too passed away.

Dave was a warm, wise and gentle soul with a streak of shining steel. He had a quick and ready laugh and a big, generous smile that began at the corners of his eyes and radiated out. He listened eagerly and with compassion. He was always interested in you, and in what you had to say. He loved sharing stories of the old days, about the Hendersons and the McArthurs and preferred to tell those rather than recount his own adventures. He knew all the old songs that his aunts and uncles used to sing at Hogmanay.

Dave reminded me of my Nana a lot. And apparently I reminded people of him. Auntie Maxie used to call me by his name. I looked nothing like him and thought the whole thing was nonsense but I guess people who knew us both recognised our kindred spirits.

One of my lasting regrets is that we never went on a bike ride together. Dave was a die-hard roadie, out doing time trials every weekend well into his 60s. My kind of cycling has, for the most part, been of the functional, get-around-town sort. I’d done a few cycle tours in Europe and completed the Land’s End to John o’Groats, but I only got into proper road cycling in my late thirties, by which time Dave was getting ready to hang up his bib shorts. I knew he and his club buddies went over to Normandy ever year for a long weekend – the Tour d’Honfleur, I think they called it – and I asked if I could tag along one year but I was politely rebuffed on the grounds of general infirmity and dwinding health among the group, not least Dave who was then struggling with various heart complications.

I did, however, get to play music with Dave. That afternoon in his music room, Dave took his guitar and started to play. I took out the clarinet and we sat and jammed together, gently, quietly. The first and only time we ever did. No Buddy Rich. No Brubeck. No legend to print. Just two kindred souls, conjuring notes in air, finding not just the joy in music, but the deeper joy of making our own.

Dave Henderson was a legend of the best kind, someone who lived his life truly and well. He was a brilliant, soulful human being with a knack for the new and a talent for excellence. He had a restless, questing mind and an unquenchable sense of adventure.

He was many things to many people, as the best of us often are, and we shall miss him dearly.